Jointly written with Alexander Goldberg.

Across domains like scientific research, education, hiring, and startup funding, decision makers evaluate a pool of applicants and then select a subset for funding, admission, or support. Historically, these decisions are usually made deterministically: evaluators assign scores, deliberate, and then select top-scoring items.

There has recently been a growing movement to incorporate randomization into high-stakes decisions. Notably, in scientific grant funding many agencies have adopted partial lotteries as a way to allocate limited funds when proposals are considered similarly strong. In a partial lottery, reviewers provide evaluations of the quality of proposals and these reviews are used to determine selection probabilities for each proposal. These partial lotteries are now used by funding agencies in New Zealand, Switzerland, Germany, the UK, Canada, and Austria. Proponents of randomized selection have cited many potential benefits of randomization. Randomization may help reduce reviewer time adjudicating tie breaks, encourage high-risk proposals, counteract “rich-get-richer”’ effects, and combat reviewer partiality [1, 2, 3, 4]. In existing deterministic peer review settings, panels often spend a significant amount of time deliberating over decisions, yet these decisions have been found to be highly inconsistent across panels [5]. In contrast, randomization can acknowledge the inherent uncertainty of decisions, while saving time on deliberations. In fact, in surveys, a majority of scientists expressed support for introducing randomization in grant funding processes, especially when used to break ties or address reviewer uncertainty [6, 7]. There have also been calls to action to implement lotteries in other competitive selection processes like college and graduate admissions. In fact, the Netherlands has used a partial lottery for medical school admissions for decades [8].

While the motivations for randomization are varied, the key question in each of these situations is:

If decision makers wish to randomize their final selections, how should they do it?

This is the question we address in our recent work, “A Principled Approach to Randomized Selection under Uncertainty: Applications to Peer Review and Grant Funding.”

Current Deployments

Existing deployments of randomized grant funding adopt various implementations of partial lotteries. Generally, these partial lotteries require the design of two parts:

(a) estimating the quality of each proposal via peer review, and

(b) making (potentially randomized) funding decisions on the basis of these estimates.

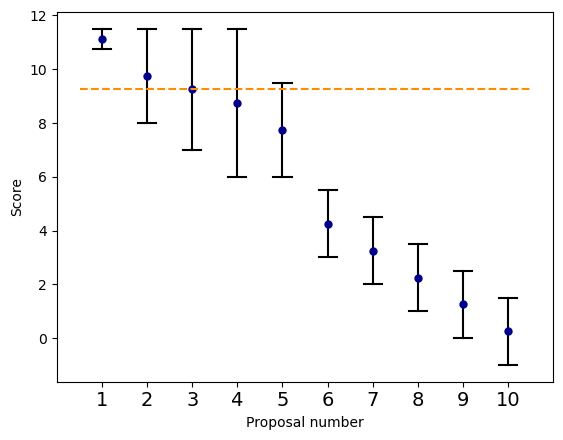

There are various approaches towards part (a). For instance, the New Zealand Health Research Council has 3 reviewers assess each proposal for acceptability of funding (a “yes” or “no” evaluation). If the majority of reviewers deem a proposal acceptable to fund, then the proposal is deemed to be “above the fundable threshold.” This is the only estimate made in this approch. Another method is one proposed and deployed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Swiss NSF) [9]. They assume a statistical model for the bias and noise of the reviewers. Under this model, given the review scores, their method then computes estimates of both point estimates and intervals for the quality of each proposal. The output of part (a) looks like:

As discussed later, our approach will allow for intervals to be generated in any way that captures the funder’s uncertainty about relative quality of proposals.

Next, we discuss the two common ways of executing part (b) — making decisions based on these estimates.

- Randomize above a threshold: Select randomly among all proposals with estimated quality above a fixed score threshold, where each proposal is selected with equal probability. This approach is followed, for example, by the New Zealand HRC.

- Triage based on intervals (Swiss NSF method): Set a funding line based on the quality estimates. Accept all proposals with intervals strictly above the line, reject all proposals strictly below, and allocate the remaining spots at random with equal probability among proposals whose intervals overlap the line.

Concretely, consider the example of 10 proposals in the figure above, and suppose a funder wishes to select 3 proposals. The funder has estimated intervals and point estimates of the quality of each proposal. Under “randomize above threshold,” the funder will select a threshold, say the score of 6 out of 10. The funder will then choose 3 proposals from the set of all proposals with point estimates of 6 or higher. Under the Swiss NSF’s method, the funding line is set as the 3rd highest point estimate as shown in the figure (more generally, the point estimate of the proposal ranked equal to the number of proposals that will be funded). Proposal 1 is strictly above the funding line and is accepted. Proposals 6 to 10 lie below the threshold and are rejected. Proposals 2 to 5 overlap the funding line so 2 out of these proposals are randomly selected with equal probability of selecting each proposal.

These existing approaches have several critical drawbacks.

(1) Randomizing above a threshold can result in unjustifiable selections where a clearly stronger proposal (e.g., with uniformly higher reviews) is rejected while a weaker one is accepted. For example, in the figure above, randomize-above threshold may set the threshold at 6 and enter proposals 1 through 5 into a lottery since they all meet this minimum quality bar. Then, due to the randomness, it is possible for 1 to be rejected while 5 is accepted, even though the funder has substantial evidence that proposal 1 is strictly better than 5.

(2) These approaches use uniform lotteries that treat all tied proposals equally, even if some have stronger support than others. In the example above, the funder has evidence that proposal 1 is of higher quality than proposal 5, but is uncertain about the relative quality of proposals 2, 3, 4 and 1. Yet, existing approaches assign equal probability of accepting proposals 2, 3, 4, and 5. A more flexible approach would use additional information, if available, to assign probabilities more gracefully.

(3) A benefit of lotteries that is often touted is that it no longer requires agonizing–and often arbitrary or biased–decisions at the boundary between fundable and not fundable proposals. Categorizing proposals into three bins (funded, lottery, rejected) instead of two (funded, rejected) still retains these boundary problems.

(4) These existing methods can be highly unstable, and even small changes in scores can shift outcomes from deterministic acceptance to complete randomization. More generally, these approaches violate social choice “axioms,” discussed later.

(5) If the statistical model assumed by SwissNSF model is believed to be accurate, then ironically, it is mathematically optimal to not randomize the decisions.

(6) Some other peer-review venues in computer science had previously experimented with statistical models very similar to the one assumed by SwissNSF, and made an effort to validate the outcomes. They concluded that these models led to poor results.

A Principled Approach: MERIT

Our approach abstracts out part (a) of computing the intervals, and allows the funder to use their choice of method. Our approach is designed to not be too closely tied to any specific model, and the intervals need not have any probabilistic interpretation. For example, the funder could simply take intervals as the range from minimum and maximum reviewer score given to each proposal, or compute bootstrapped estimates, or accommodate subjectivity in the reviewer recommendations, etc. This makes our approach particularly applicable to settings where decision-makers have so-called “Knightian uncertainty”—that is, when they cannot assign probabilities to possible outcomes. This approach is apt for grant funding contexts, where we lack realistic and well-validated probabilistic models of the review process. We discuss a number of possibilities for how to generate intervals from review data in our full paper. Essentially, the funder should choose an interval-generation method that reflects their judgment about when the available evidence is sufficient to conclude that one proposal is better than another (namely, when the corresponding intervals do not overlap).

The focus is on part (b) — making potentially randomized funding decisions given the intervals. We propose a novel optimization-based approach that seeks to address limitations of prior methods. Our algorithm, which we call MERIT (Maximin Efficient Randomized Interval Top-k) seeks to ensure two principles of ensuring robustness under uncertainty and ensuring justifiable outcomes, outlined below. The principles are based on a simple interpretation of quality intervals — if proposal A has an interval that lies strictly above proposal B, then the funder has sufficient evidence to conclude that proposal A is stronger than B. However, if A and B have overlapping intervals, then the funder lacks sufficient evidence to conclude based on this comparison between A and B which proposal is of higher quality. Then our randomized decisions aim to respect any certainty, and acknowledge any uncertainty via randomness, where uncertainty is captured by the quality intervals.

Principle of Ex-Ante Optimality: Ensuring Robustness under Uncertainty

When faced with uncertainty, how can a decision-maker act in the most responsible way? In the absence of uncertainty, a funder would select the highest quality proposals within their budget. However, when quality intervals overlap, a funder lacks sufficient evidence to definitively rank one proposal over another. Any ordering of these tied proposals is plausible, so simply picking the one with the highest point estimate is an arbitrary choice that ignores this fundamental uncertainty. A simple lottery, on the other hand, treats all tied proposals as perfectly equal, even when some have clearly higher potential than others.

The principle of Ex-Ante Optimality offers a robust path forward. Instead of hoping for the best, it confronts uncertainty head-on by asking the question: “What is the most unfavorable ‘true’ ranking of proposals that could occur, given our uncertainty?”. Specifically, we consider any ranking of the proposals consistent with their overlapping intervals to be a feasible ranking. For example, in the intervals from our running example, proposals 2 to 5 all have overlapping quality. So, any ordering of these proposals is consistent with the intervals. However, proposal 1 lies strictly above all other proposals and therefore must be ranked highest in all feasible rankings. Hence, the top 3 highest quality proposals could be proposal 1 and any subset of two proposals among 2 to 5.

Then, we aim to design an algorithm that selects a high number of the true highest quality proposals even in the worst case ranking consistent with the intervals. This maximin optimization naturally leads to randomized selection strategies. When we can’t definitively distinguish between proposals, the optimal approach is to give each a selection probability that reflects both their potential quality and the uncertainty in their relative quality.

Principle of Ex-Post Validity: Ensuring Justifiable Outcomes

The second principle, ex-post validity, guarantees that final selections are always justifiable to stakeholders. Specifically, if we select a proposal with a lower quality interval, we must also select any proposal whose interval clearly dominates it.

This prevents embarrassing scenarios where a funding agency rejects a proposal that dominates an accepted proposal in quality. Such outcomes would be indefensible to applicants and undermine trust in the selection process. While this principle may seem obvious, the existing randomize-above-threshold method does not obey the principle. For example, in the New Zealand Health Research Councils’ approach there may be one proposal that is clearly better than the other, but both are entered into a lottery as they are deemed above a minimum threshold for quality. In this case, the lower quality proposal may be randomly selected while the higher quality proposal is randomly rejected.

An efficient algorithm

Designing a computationally efficient algorithm to simultaneously satisfy these two principles is technically challenging. Many related problems in the Computer Science literature are known to be computationally intractable (most notably, a generalization of our problem known as the minimum weight k-ideal problem). We develop a novel algorithm that we mathematically prove meets both criteria and is computationally efficient, running on over 10,000 proposals (based on peer review data from a real conference setting) in under 5 minutes on a standard personal laptop.

Comparing Methods: An “Axiomatic” Framework

When choosing the best grant proposals or college applicants, how do we know if one selection method is better than another? In the setting of scientific grant funding, there’s not reliable “ground truth” for what makes the best choice. Thus take an “axiomatic” approach which is popular in economics and social choice: we identify key principles (“axioms”) that any reasonable selection method should satisfy, and then evaluate competing selection methods for these axioms. We propose three axioms for randomized selection and mathematically prove that MERIT satisfies the first two, while existing methods do not.

1. Stability

The principle: Tiny changes to only a single proposal’s quality estimate shouldn’t flip the algorithm’s output between completely random selection and completely deterministic selection.

Swiss NSF and randomize-above-threshold are maximally unstable, whereas we prove that the MERIT algorithm is not.

2. Reversal Symmetry

The principle: If you reverse the quality scale (so high becomes low and vice versa), the selection probabilities should reverse accordingly.

Our MERIT method handles this symmetry correctly, while other existing approaches do not.

3. Monotonicity in Budget

The principle: If a funding agency increases their budget to accept more proposals, no proposal should become less likely to be selected.

This seems obvious, but surprisingly, all randomized selection methods we consider fail this basic requirement. In fact, when simulating the selection algorithms on real data from the Swiss NSF’s 2020 grant funding process, we find that both the Swiss NSF method and MERIT violate monotonicity — increasing the number of proposals funded can decrease the probability of selection for some proposals.

We also provide a modification to MERIT to ensure monotonicity in budget, but this may come at the expense of worst-case optimal utility.

In summary, our mathematical analysis shows that MERIT is more stable than existing methods and satisfies reversal symmetry. Moreover, our “axiomatic” framework for comparing selection algorithms can prove useful in evaluating alternative randomized selection methods going forward.

Comparing Methods: Empirical Simulation

Beyond mathematical analysis, we empirically evaluate how these algorithms perform in practice via simulation. To do this properly, we need to know the “ground truth”—which proposals are actually the best—so we can measure how well each algorithm identifies them. For the evaluations, we use real peer review data from scientific funding agencies and conferences as the foundation, then generate synthetic datasets where we control the true quality rankings while preserving realistic review patterns.

We evaluate algorithms from two perspectives:

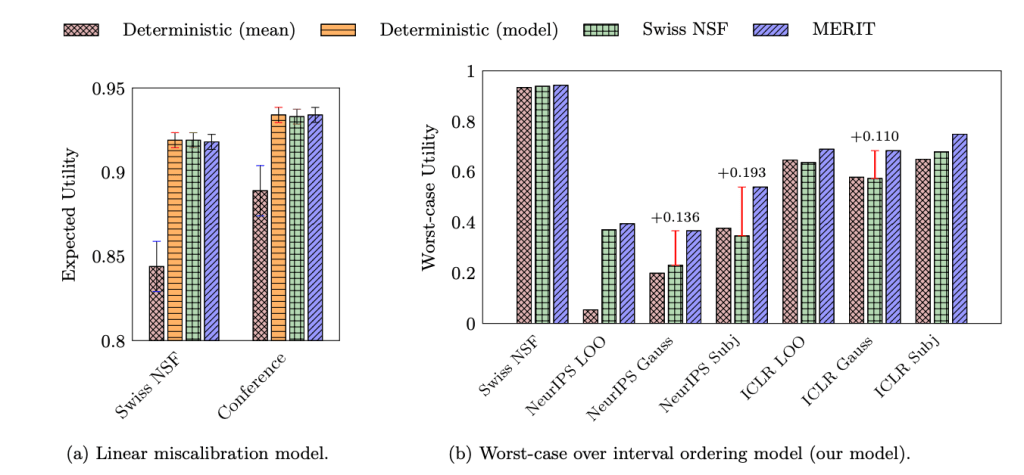

What if popular modeling assumptions are correct?: How well does the algorithm work in expectation under a probabilistic model of how reviewers generate scores given true quality? We adopt a linear Gaussian miscalibration model, which has been employed in many prior works including by the Swiss NSF.

How robust are selection mechanisms under uncertainty about the quality of proposals?: The linear model used by the Swiss NSF and others has been tried in many settings, and has often been found to perform poorly based on inspection of adjustments to review scores made by the model [5, Section “miscalibration”]. Given that there are no good models for such data, this suggests that we should not have our methods/decisions tied too closely with any specific model. In our work, we ask how to make robust decisions under uncertainty. We assume that any ranking consistent with quality intervals could be the true ranking. This measures performance in the worst possible case, which is the objective optimized by MERIT.

We generate datasets based on the Swiss NSF’s real review process from 2020 and conference data from the large-scale computer science conferences NeurIPS 2024 and ICLR 2025. For the worst-case expectation over ordering of intervals, we use the Swiss NSF’s method for generating intervals on their data and test three different methods for generating intervals for NeurIPS and ICLR.

As shown in the bar chart above, under the Swiss NSF’s probabilistic model, MERIT performs just as well as existing methods. It matches the performance of the Swiss NSF’s randomized approach and deterministic selection using model-adjusted scores. All three methods out-perform deterministic selection with the mean score, which does not account for reviewer errors. This is encouraging—our algorithm doesn’t sacrifice expected performance for its robustness benefits.

MERIT exhibits substantially more robustness than existing approaches, yielding much better utility in a number of settings. By design, MERIT obtains the optimal worst-case utility. Interestingly, the optimality gap between MERIT and Swiss NSF or deterministic selection can be quite large, up to 0.193 higher worst-case utility for NeurIPS subjectivity intervals, for example. These results suggest that our approach offers reliable performance in typical situations with improved robustness under uncertainty.

Avenues for future work

The MERIT algorithm provides a principled approach to randomized selection that exhibits desirable axiomatic properties and performs well both in expected utility under a popular probabilistic model of reviewer error and in worst-case scenarios. However, like any method, it has limitations that point toward interesting directions for future research.

In particular, future work may include handling variable funding amounts for different proposals, incorporating additional information about proposal comparisons beyond intervals, extending to richer utility functions beyond top-k selection, and understanding how randomization may impact applicant and reviewer behavior in equilibrium. These research directions can help bridge the gap between theoretical understanding and practical deployment of randomized selection systems.

Full paper: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.19083

Code: https://github.com/akgoldberg/lottery

References:

[1] Koppel, M., Schettini, N., & Bouter, M. (2022). Partial lottery can make grant allocation more fair, more efficient, and more diverse. Science and Public Policy. https://academic.oup.com/spp/article-abstract/49/4/580/6542962

[2] Carnehl, C., Ottaviani, M., & Preusser, J. (2024). Designing Scientific Grants. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series. https://www.nber.org/papers/w32668

[3] Fang, F. C., & Casadevall, A. (2016). Research Funding: the Case for a Modified Lottery. mBio. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27073093/

[4] Feliciani T., Luo J., & Shankar K. (2024). Funding lotteries for research grant allocation: An extended taxonomy and evaluation of their fairness. Research Evaluation. https://academic.oup.com/rev/article/doi/10.1093/reseval/rvae025/7735322

[5] Shah, N. B. (2022). An Overview of Challenges, Experiments, and Computational Solutions in Peer Review. arXiv preprint. https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~nihars/preprints/SurveyPeerReview.pdf

[6] Liu, M., Choy, V., Clarke, P., Barnett, A., Blakely, T., & Pomeroy, L. (2020). The acceptability of using a lottery to allocate research funding: a survey of applicants. Research Integrity and Peer Review. https://researchintegrityjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s41073-019-0089-z

[7] Phillips, A. (2022). Research funding randomly allocated? A survey of scientists’ views on peer review and lottery. Science and Public Policy. https://academic.oup.com/spp/article/49/3/365/6463570

[8] Cate, T. (2021). Rationales for a Lottery Among the Qualified to Select Medical Trainees: Decades of Dutch Experience. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8527950/

[9] Heyard, R., Ott, M., Salanti, G., & Egger, M. (2022). Rethinking the Funding Line at the Swiss National Science Foundation: Bayesian Ranking and Lottery. Statistics and Public Policy. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2330443X.2022.2086190